|

|

Farm

at a Glance:

NuTech Farm

Location:

The Kutch district on India's western coast. NuTech

farm is located in the Rayan village 9km from

the seacoast town of Mandvi.

Farm Type:

Organic

Size: 42 acres

What is grown: Aloe

vera, dates, amla, melons, millet, castor beans,

mungbean, pigeon pea, vegetables and select medicinal

plants.

|

|

The NuTech bodyguards:

Shah intermingles various crops, such as the castor beans

shown here, to keep disease and pests away from his aloe plants.

|

"“I’m not the boss here... maybe the

conductor,” says Vijay Shah. “The different players all

contribute in their own peculiar way, from friendly bacteria

and mycorrhizae to termites, earthworms, bats, frogs,

lizards, birds, cattle, dogs and so on." |

|

|

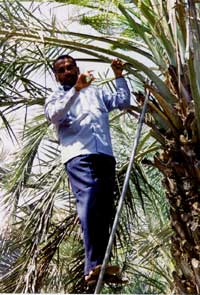

Delightfully sweet dates

Vijay Shah thanks his father, who died 5 years

ago, for developing dates into a family specialty.

Able to do little else in his old age and ailing

health, his father traveled to the best date farms

in their district of southwestern India. He sampled

date varieties to bring home the best ones in

large quantity. Shah's mother and wife cut up

the dates, planted the seeds, and then distributed

the sweet parts of the fruits to the whole village.

Through rigorous selection, NuTech Farm now produces

date varieties that are remarkably sweet and delicious.

“These are actually my father's legacy,” says

Shah.

|

|

|

|

|

Acres of aloe: Some

of Vijay Shah's 30 acres of aloe vera plants in southwestern

India. |

|

Posted April 22, 2003: In westernmost India,

bordered by Pakistan and the Arabian Sea, lies the tortoise

shell-shaped desert region of Kutch.

The sun beats down mercilessly on brittle scrub brush, cacti,

and salt flats. Rain comes only two or three times a year.

It crashes down in torrents, carving channels through the

cracked, sun-dried soil, racing to the sea before it has time

to soak in.

Last year the region received rain only once – a 3-inch downpour

after two unusually dry years. Kutch sustained massive destruction

from a 2001 earthquake that scored a 7.9 on the Richter scale.

Despite these harsh conditions, farmers continue squeezing

crops out of the begrudging, sometimes forbidding land. A

growing number have decided to work organically precisely

because of these difficult circumstances.

One of these pioneers is Vijay Shah, 45, a bearded, man with

a quick smile. He owns the 42-acre “NuTech Farm,” specializing

in fresh dates and aloe vera. Though he used modern fertilizers

and pesticides for years, there is a commemorative piece of

paper taped to his desk with the penciled note, “1 July 1996:

stopped using chemicals completely.”

In the violent desert climate, Vijay Shah has created an

oasis of peace -- for himself, his extended family, and his

land.

Many influences, from Gandhi to

grandma's blessings

|

|

| Hot dates

: Shah uses boiling water in lieu of chemicals

to keep harmful insect populations from ruining

his fruit trees. |

|

Shah’s transition to organic farming was gradual and with many

influences. He compares his situation to the story of a fool

who found himself in a well rescuing a child who had earlier

fallen in. When they both were safely out, the fool was met

with congratulations for his bravery, but responded in irritation

and confusion. “First tell me who pushed me in.”

“I’m still trying to figure out who pushed me in,” Shah says

with a laugh. “Was it my readings of Schumacher's 'Small is

Beautiful,' or Alwyn Toffler's 'Third Wave,' or Gandhi's 'Rural

Independences,' or my Grandma's blessings?”

After spending five years of his childhood with his grandmother

in the small village of Rayan, in southwestern Kutch, Shah

spent most of his early years in Bombay (now Mumbai). He graduated

from college with a degree in printing technology in 1977

and soon after started a printing business with his brother.

Within a few years he began to feel restless. “I could see

that I wasn’t a good businessman,” Shah admitted. “Deep in

my heart I had the inkling that I must work with the soil,

with Mother Nature.”

Looking for a more peaceful existence for him and his father

-- who had recently suffered a heart attack – he and his wife

moved to 4 acres of ancestral land in Rayan village in 1986.

They lived with his father and mother, and began growing crops

of sweet corn, melons, pomegranates, figs and dates.

Vijay Shah started farming with chemical fertilizers and

pesticides. Production was exceptional. “In those days of

fertile soil and available water we had beautiful dates and

shining red pomegranates. We produced up to six times more

than other farms.”

After seven years of synthetic inputs, however, Shah realized

what other farmers in the region are now beginning to understand

-- that chemical farming in their harsh conditions cannot

last. Because the chemical fertilizers he used provided nutrients

only for the plant, his soil structure was weakened. He saw

he had killed many of the beneficial organisms that make the

soil porous and fertile so it can absorb moisture. The soil

lost its finer particles, becoming dead and hardening when

it rained.

During the dry season, wind blew the cracked, dusty topsoil

off his land. When the torrential rains came, they washed

loose soil into flash-flood rivers.

To make matters worse, Shah’s neighbors began growing cotton.

Their reckless pesticides use drove insect pests to seek refuge

at NuTech Farm. He was at a crossroads. “I had to make a decision

– whether to continue the vicious cycle of using more and

more chemicals, or change my whole way of farming,” he said.

Seeking peace, changing paths

|

|

|

Plants of the sea feed under-nourished

soil

The brown black seaweed (saragassam wighti) is

harvested about 1 km off the coast of the Gulf

of Kutch and brought back to the farm for processing.

The harvested crop is dried in the hot Indian

sun then run through a thresher which separates

sand and other unwanted stuff and grinds the seaweed

into coarse powder grade. The powder is then packed

in poly bags (30kg each) and stored. The powder

provides additional nutrients to the dry soil.

It can be used as a soak or as a spray. In a year,

NuTech uses 2 tons of seaweed for 30 acres irrigated

land; an additional 6 tons is sold to other farmers.

|

|

Soon after, Shah entered a Vipassana meditation course that

proved to be a turning point in his life. (Vipassana means “seeing

things as they really are.”) A guru gave him counsel that gave

him new insight: “If you’re really looking for peace, then your

livelihood should be peaceful."

Shah realized that instead of the relaxing existence he had

sought in the country, he was experiencing constant anxiety

about his farming life. He was always trying to kill what

he saw as harmful insects -– especially the pesky, resilient

termites. He worried continually about marketing and his steadily

decreasing production.

“I was very stressed. I had to keep using chemicals but the

response was declining,“ he said. “I was scared and asked

myself, ‘What will happen if I stop?’”

As he continued with meditation, Shah began to decrease the

amount of chemicals he applied. “For three years it was very

tough. I didn’t have any information on what to do in the

transition period,“ he said. “They said to stop using chemicals...

but what are the alternatives? It took me a long time to understand

the phrase, ‘healthy soil for healthy plants’.”

Throughout production declines during this period, Shah gradually

began to figure things out. He built up the soil, eventually

developing a set of eco-friendly inputs. The products he uses

and markets to others to maintain soil and plant health include

the plant-based products neem, karnalia, calotropis, euphorbia

and whole aloe. From the Gulf of Kutch he harvests brown seaweed

and green algae. He uses nutrient-rich cattle urine through

his drip irrigation system.

Shah took other steps to protect his soil and shelter plant

life. He mulched more and began leaving low-lying weeds around

plants as living mulch. He planted more trees to lower soil

temperature so it would be more conducive to micro-organic

activity. He planted mixed varieties of specialty trees, such

as neem, sesbania, drumstick trees (Moringa oleifera) and

five-leaved chaste tree (Vitex Negundo) as wind breaks for

his soil. He abandoned use of poisonous fumigants to kill

pests that attacked trunks of his date trees. Now he pours

boiling water in crevices of trunks in affected trees, killing

only harmful insects.

Shah’s new attitude changed the way he looked at termites.

Once he stopped trying to kill them all, he saw they were

benefiting him by breaking down dead matter and providing

good aeration to tree roots. “They don’t eat anything green,”

he said, admiring their work in the trunk of a date tree.

“Now termites are my best friends.”

Shah’s efforts produced results after several years. Plants

grew stronger and gave more fruit. Improved soil held more

moisture. Shah estimated that during one 3-inch downpour his

smaller tract of land retained twice the water of his neighbor’s

chemically farmed land, judging from the reservoirs that receive

the run-off from the ditch system on each farm.

Booker T. and aloe vera

|

|

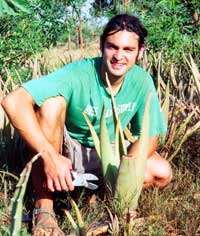

| Convening with the natives:

Thriving in hot dry climates, the aloe vera plant

has found a natural habitat on Shay's farm. Pictured

here: author Jason Witmer. |

|

Shah gleaned some agricultural wisdom indirectly from African-American

educator Booker T. Washington, an idol of his. Washington tells

the story of a ship that was caught in a hurricane off the coast

of South America. When all the ship’s water was gone the distraught

captain radioed in for help from shore. He received the simple

SOS: “Drop your pail where you are.” At first disbelieving,

the captain eventually discovered that the seawater there was

sweet because it comes from the mighty Amazon River, which pours

freshwater into the sea for miles at its mouth.

The story made Shah think about his own life. “There I was

bringing pomegranate plants from 2,000 kilometers away,” Shah

realized. “I was buying sweet corn and melon seeds from U.S.

and Taiwan – everything from such distances. I wasn’t dropping

my pail where I was.“

The day after reading that story, Shah stopped at the gate

in front of his farm and noticed a small patch of aloe vera

plants, growing happily with no human management. Though he

had little knowledge of the potential market, and still less

about how to process the aloe products, he decided to "drop

his pail there." Shah had heard of its uses in ayurvedic healing

and saw advantages in raising a crop that seemed be able to

take care of itself.

He found little information existed for on-farm processing

of the long succulent aloe vera leaves. He and his wife began

experimenting in their kitchen to learn how to extract the

valued gel.

As he expanded production he experienced new challenges.

To counter plant-rot in low areas after the monsoon, Shah

turned to a bed-and-furrow system that he extended to nearly

his entire farm. He planted medicinal Malabar nut (A. Vasica)

trees as a natural irrigation indicator. These help him restrict

water to the minimum that keeps the gel value highest. He

controlled weeds by letting the cattle graze rotationally.

He controls diseases and pests by intercropping the aloe vera

with plants such as dates, amla (Indian gooseberry), melons,

millet, castor, mungbean, pigeon pea, vegetables and selected

medicinal plants.

After four years of trial and error the couple perfected

a suitable extraction and stabilization process. Shah’s brothers

converted a small building into an aloe vera processing plant.

They began marketing aloe vera to cosmetic companies and continued

to improve the quality of their aloe gel.

Manish, Vijay's younger brother, worked to develop a health

drink from their aloe gel. Manish joined 40 scientists from

26 countries in China to interact on aloe use. He returned

with the confidence to prepare six specialty health beverages

with selected medicinal herbs.

Mahendra, their elder brother, is using his marketing genius

to expand production to the European Union next year. At times,

all 17 members of Vijay’s family work together at times to

keep the aloe activities going.

Shah has expanded to 30 acres of aloe vera. He continues to

fine-tune production skills to maintain production even in

dry years such as 2003, where plant color will be diminished

but production remained constant. The date trees, which usually

decline after a few years under chemical fertilizers, are

producing so well that he has named many of them. “They’re

like family members,“ he said.

Shah is helping to develop an organic certification system

for small farmers of India. Right now Shah can only market

his products to people who know him well. With an organic

certification system both he and smaller farmers with fewer

connections could market to anyone. He is on of 35 Indian

organic farmers who hope to draft guidelines for a certification

system by the end of this month.

Regenerative agriculture has given Shah new hope for his rural

life. He is grateful to still be in business. “Many farmers

are tired,” he said. “They’re feeling like they can’t do this

anymore. They’re thinking about doing something else -– maybe

opening a stand and selling cigarettes or something like that.

But I am still farming.“

Shah appreciates most, however, the contentment that he finds

by co-operating with his environment rather than ceaselessly

fighting it.

“I’m not the boss here... maybe the conductor,” Shah figures.

“The different players all contribute in their own peculiar

way, from friendly bacteria and mycorrhizae to termites, earthworms,

bats, frogs, lizards, birds, cattle, dogs and so on. When

that kind of harmony develops there is a reverence for each

other. Initially, I was always tense, worrying, killing –

but now I have peace."

Coming next: Meet a doctor with the organic

medicine to keep his farm cool and irrigated even in the Indian

desert. Doctor Haria, an alternative agricultural physician

and Mr. Shah's mentor, also has a cure for acne that American

teenagers may not be ready for…

|